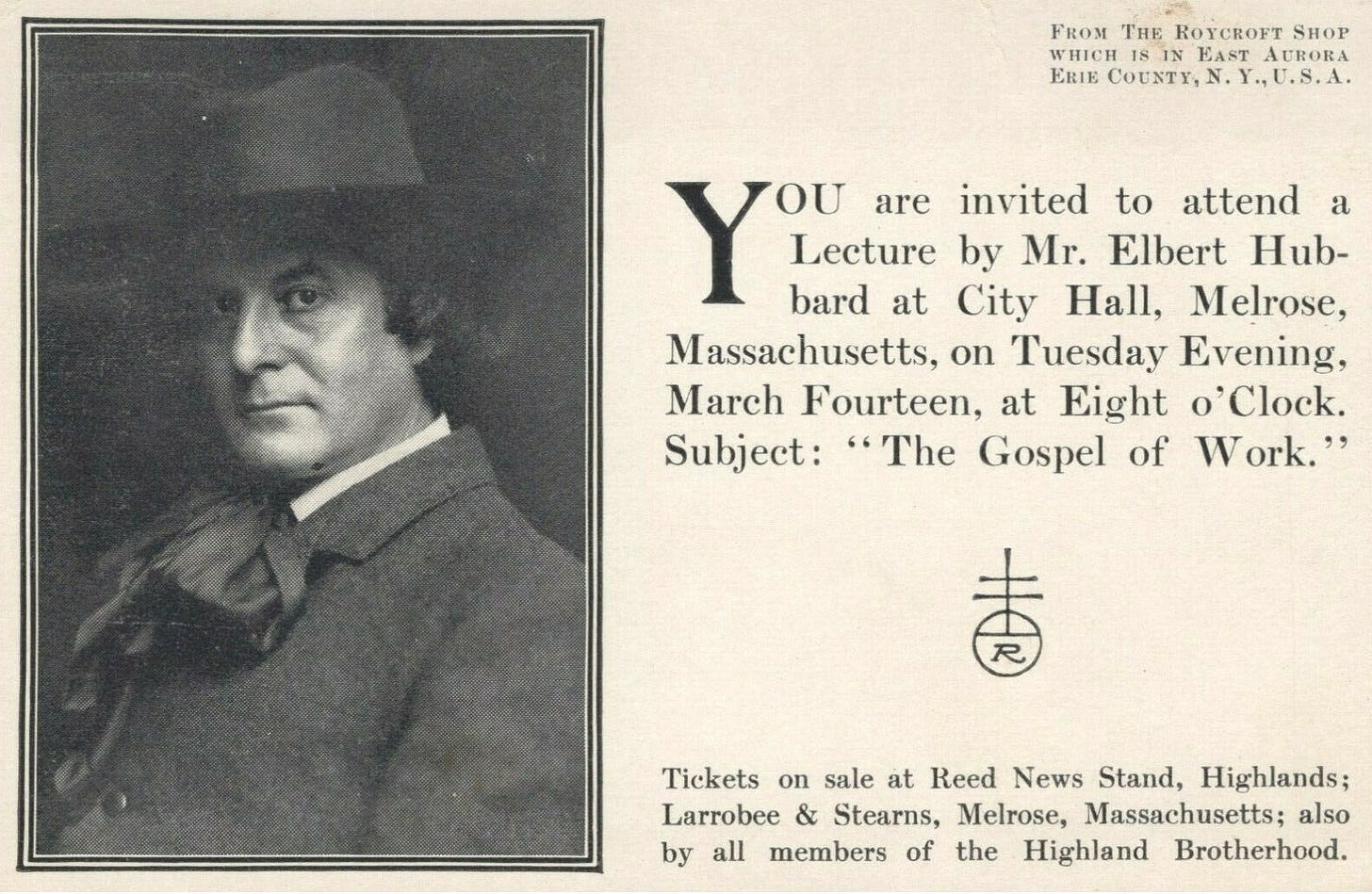

I have a most peculiar affection for Elbert Hubbard. He was, as the elderly will recall, the author of that capsule classic of the Mauve Age of Americana, A Message to Garcia. When not traveling about the country on the lecture platform, taking innocuous pokes at the clergy—at a time when taking pokes at the clergy was considered next to blasphemy—he conducted the institution at East Aurora, N.Y., known as the Roycrofters. Between times he published a monthly brochure known as The Philistine. Authorities wise in the art of letters have been kind enough to proclaim that only two concerns in America in the first half of the Twentieth Century have known what beautiful printing was, and produced it. One was The Roycrofters and the other the various Pelley enterprises. The Roycrofters books and the Libreation-Soulcraft books have been pretty much on a par, say they. A bibliophile in Michigan recently made me the invaluable present of a whole file of bound The Philistines, and I renewed my acquaintance with Fra Elbertus. It was by no means a synthetic or vicarious acquaintance. I knew Fra Elbertus in person. And the acquaintance held a touch of adolescent poignancy..

Early I had discovered Fra Elbertus and his anti-clerical effusions when A Message to Garcia had been published. Hubbard, according to his own accounts, had been especially riled at a heel-dragging employe in his East Aurora printery whom he’d instructed to do a certain thing and who had returned a barrage of questions and objections when directed to it. Banging into his writing-room—as I have so often banged into mine—he sat down and Took His Pen in Hand. He wrote a couple of red-hot ziggities in the way of paragraphs about the man who can take instructions and Not Talk Back. One George Daniels, passenger agent of the New York Central, read it and gave Three Cheers. He had the thing reprinted in hundreds of thousands and it made Hubbard famous. Came the day when, in the eighth grade of grammar school, I returned from noonday lunch to find a big chunk of A Message to Garcia done in chalk on the blackboard by Teacher. All of us small fry were supposed to memorize it. The least I can say in praise of it was, that it did us no harm. Next I discovered a copy of The Philistine in the Springfield Public Library. I was a Hubbard fan from that lucky moment onward. When, in the exuberance of the ripe age of 13 I set up my own stable—or I might put it, horse-barn—printery and issued The Junior Star, hand-set and foot-kicked on a Pilot Press, I sent a copy to Fra Elbertus to acquaint him with the fact that I too was on earth and engaged in the vocation of arranging metal types to convey human intelligence. To my stupefaction, did an embossed envelop come back from East Aurora—which was, and is, a country bailiwick not unlike Noblesville, south of Buffalo in Upper York State—complimenting me on the publication and enclosing one of Uncle Sam’s paper dollars for a year’s subscription. A man as big, and internationally known, as Fra Elbertus had taken time out from a busy life to read a small boy’s smudge-sheet and visualize what a whole dollar paid by one subscriber could mean. It was like having Gutenberg, Benjamin Franklin, and the Lord God send me a year’s subscription. Rocked along maybe six months and in a barbershop window on State Street glowed a placard telling the citizens of that city—Springfield—that on the 27th of October none other than Fra Elbertus, famous author of the Message to Garcia and editor of the Roycroft publications, would stand in the rostrum of the Art Museum Hall and deliver words out of the mouth that was presumably in his face, for which the admission charge was fifty cents to hear them. So!.. Gutenberg, Franklin and God were coming to the city of mine adolescent residence and talking to the General Public from the rostrum of Art Museum Hall. All of Snazzy Springfield would turn out, I was certain. Likewise I would turn out if I had to burglarize a penny gum-machine to get the coins. Came the roseate night of the 27th and I did turn out. I turned out at 6:30 p.m. and was the first patron to relinquish three dimes and four nickels from my hot little fist that I might have my pick of the 800 empty seats, one-fourth of which were situated in the balcony at the back. I solemnly affirm that upon gaining to the Art Museum precincts I did not choose my chair up in the balcony at the back..

Yes, indeedy, I was there. I was there at 6:35 in the front row of chairs on the lower floor, as near to the platform as I could get and not be taken for Fra Elbertus myself by patrons who entered after me—with an hour and forty-five minutes to wait before the mouth that was in the Hubbard face opened and words came out, pokes at the clergy or otherwise. And while wiggling off the small of my back, because of the hardness of the seats—that were already unbearable long before seven o’clock arrived—who should be the second entrant into the hall but Gutenberg, Franklin and God himself, dressed in that inimitable Prince Albert, Stetson, and Buster-Brown haircut. Presumably these had entered ahead of time to scout the patronage, or anticipate the Gate. I looked, I froze, I opened many mouths in my own face and knew exactly how it felt not to have speech issuing from a single one of them. All these celebrities were coming toward me. They showed interest in the Early Patron in corduroy knee pants. “Hello, Sonny,” said the Gutenberg-Franklin-God trio, “you’re here early. What might your name be?”.. Somehow I gasped that I had been christened William Dudley, that the last name was Pelley, and that I was pleased to meet him. Also I started to add something about my proprietorship of the aforesaid Junior Star. Did Great Man remember? He most certainly did. “Well, well, well!” he exclaimed—and the interest in his lustrous brown eyes was bona fide. Whereupon, for the first and only time that I’m aware of in this current vale of tears, I had God sit down beside me, put his arm about my shoulders, pat me in complimentary motif, and talk excellent printing to me for almost an hour before he got up on the platform four feet away and opened the mouth that was in his face to talk to bigwig Springfieldians at 50 cents the wig.

If you happen to have a bound set of Little Journeys in your home, take down the volume on Great Musicians and read Hubbard’s Journey to the home of Guiseppe Verdi, the immortal composer of Aida. In it Fra Elbertus describes the boy Verdi, “ten goin’ on eleven”, lying at the foot of the garden wall of the great Signore’s house and listening to the Signore’s daughter playing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. Just a ragged little urchin, staring up at the lighted windows of the great Italian mansion as though seeking to see the music as well as hear it. Suddenly, “Do you like music?” came a voice from behind. The boy turned and looked up at the kindly face of Signore Barezzi, owner of the premises. The boy stammered out that music was his soul and his life. And the Signore said, “That is my daughter playing; come inside with me.” The hand of the great man reached down and the urchin clutched it as though it were something he had long been waiting for. They walked through the big gates where the stone lion kept guard on either side. Into the great house the ragged little future composer of Il Trovatore, La Traviata, Rigoletto, and Aida, went, and became the great musician that he did become because the Signore had been kind to him.. Well, I like to think in my overly sentimental moments that I lived precisely that saga with the man who wrote the Little Journey to the Home of Guiseppe Verdi.. But time rocked along and came the afternoon in the Bennington Banner office, just as we were going to press, that the news bulletin arrived that the Germans had torpedoed the Lusitania and Elbert and Alice had stood together on the ship’s sloping deck, his arm about her waist, refusing to leave each other for the life boats, keeping their rendezvous with Splendor in close company. He would, and they would. So Fra Elbertus was no more, excepting as a nostalgic idyl in my memory. He had talked with me alone for an hour before facing a great audience once, talked with me about Good Printing.. Time rocked along still further and came the day when I sat in the palatial drawing room of his nephew, one John Larkin of the Larkin Soap Company of Buffalo—one of the original Soulcraft supporters, by the way—and had John say to me, “Pelley, why don’t you go down to East Aurora and buy the Roycroft plant? I can fix it so you can get it.” Well, next day I did go over to East Aurora, my first visit there, by the way, and wandered through the dusty rooms of Roycroft, the monotypes looking frowsy and the Whitlocks presses rusty. There were webs of the spider in the once-famous bindery, and over in Roycroft Inn the mission furniture was battered like the desks of an old village school.. I never did go through with the deal to acquire Roycroft, although I do have my moments when I’m sorry that I didn’t. But the beauty of the Hubbard printing has stayed with me, and I have tried to make books that were a credit to his memory..

Friends, it forever pays to be kind to the little boys, not born into proficiency of this world’s goods, who look up at the lighted windows of the great Signore’s mansion from which the Heavenly Music is coming, or who gaze in aphasia at the personage of the Great Man sitting down beside them and giving them a whole hour of his personal attention to discourse privately and personally with them on Good Printing. When you do such kindly things, from the grandeur of your mortal renown, you may be planting myrtle to your own worthiness in the Garden of the Anointed. I have tried to make the Soulcraft books the most beautiful specimens of the letter-press art to be found in America. Here and there I have failed. Not always have I been able to get the Boys and Girls to revere Beautiful Printing as I revere it. But I love Elbert Hubbard. He was a Great Soul who did a Great Work. The world thinks of him as a drawing room iconoclast of the Mauve Decade. I think of him as a sentimental giant who knew what was passing in the heart of a boy and sent him one dollar in Uncle Sam’s cash to enable him to go ahead with his boyhood dreams that were to culminate in the nation getting the Golden Scripts. Yes, be kind to the wistful-eyed boys who look up at the Lighted Windows and dream their dreams. They be riders of Pegasus in another generation. And each generation needs them… What an exquisite time I’m going to have talking with Fra Elbertus about Beautiful Printing when I too go through my own Lusitania without deserting a Help-Mate Woman. And further deponent sayeth not.. –THE RECORDER

That old synchronicity always in effect, The Ephemera Society posted this item about the Roycrofters today: https://www.ephemerasociety.org/the-roycrofters-the-roots-of-protest/