"The fleshpots of Hollywood. Oriental custodians of adolescent

entertainment. One short word for all of it--JEWS!

"Do you think me unduly incensed about them? I've seen too many

Gentile maidens ravished and been unable to do anything about it. They

have a concupiscent slogan in screendom: `Don't hire till you see the

whites of their thighs!'

"I know all about Jews.

"For six years I toiled in their galleys and got nothing but money."

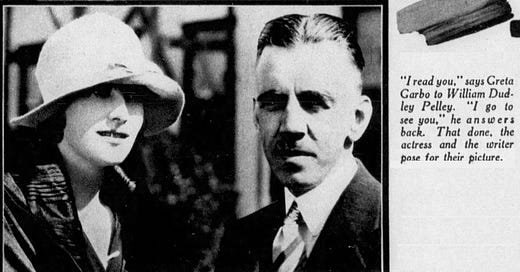

So writes William Dudley Pelley of his career as a silent-era

screenwriter. He had written for 21 films and made $300,000 by his count

working for every major studio except Paramount. By the time his novel

Drag appeared on screen as one of Warner Brothers' first talkies

(1929), Pelley had severed all ties with the motion picture industry.

The passive antisemitism he had shared with many Hollywood figures

was heating up and would come to a boil the last day of January 1933

with the launching of The Silver Legion of America. The Legion, coming

into national notoriety as the Silvershirts, marched off on a seven-

year campaign against communism in general and Roosevelt's "Jew Deal"

in particular. Accusations that Pelley was on the Nazi payroll were

disproven, but he found much support among members of the German-

American Bund, a group of U.S. fans of the new German government.

Although few of his old friends from Hollywood would openly support

Bill Pelley's Silvershirts, his tirades against the Jews could have

hardly surprised those who knew him well. Pelley's low opinion of Jews

had been established in the latter months of 1918 when he served as a

YMCA scout in Siberia.

"I had [been in] Russia during the worst introductory phases of the

Bolshevist Revolution. What I saw or learned in Russia in consequence

opened my eyes to what I believed to be the modern program of the

Israelites, and I became openly anti-Semitic in consequence."

Back in the States, Pelley resumed his career as a successful

freelance writer for such magazines as Saturday Evening Post,

Cosmopolitan and World Outlook. In 1921 Pelley received a note from

Karl Harriman, editor of Redbook, concerning a three-part serial he had

submitted. Harriman reported that, while he wouldn't be using White

Faith, he had taken the liberty of forwarding the story to New York

movie agent Larry Giffen. Pelley said he thought little of it until a

letter arrived from Giffen announcing, "I can get you $7,500 for the

screen rights to White Faith."

Pelley went to New York where he spent the next two weeks with

director Clarence Brown transforming his story into the script for The

Light In the Dark (1922). Jules Brulatour foot the bill for the

$175,000 production, insuring that his girlfriend, Hope Hampton, spent

more time on screen than her more talented co-star Lon Chaney.

Lon and his wife Hazel were regular guests in the home of Bill and

Marion Pelley until filming was completed on Christmas morning 1921.

Pelley's daughter Adelaide, just seven years old at the time, fondly

recalls one of Chaney's visits.

"He came to dinner, bringing my mother a box of chocolates. After

dinner he called me over to his side and put one of the little brown

crinkled cups into each eye socket to give me my own personal little

horror show. I was enchanted, of course, and didn't know for years that

he made his living that way."

Lon soon returned to California, taking with him another Pelley

script, The Shock (1922), which the two had prepared from Pelley's

Munsey Magazine story "The Pit of the Golden Dragon." Two weeks later a

telegram arrived for Pelley.

"CARL LAEMMLE OFFERS TWO THOUSAND FOR SHOCK. WIRE ME. NO REGARDS.

LON."

Puzzled by Lon's lack of regards, but excited at the prospect of

working in Hollywood, Pelley wired him to close the deal. Chaney picked

him up at the train station ten days later.

"You danged fool," Chaney scolded, "you euchered yourself out of

three grand. Didn't I specifically say to wire me No! ... or didn't you

grasp I wanted to use your refusal to jack the price higher for you?"

The telegraph operator had flubbed the punctuation and Lon's

intentions were lost in the wire.

"However," Pelley said, "I was too glamoured with what I presently

experienced to sue the Western Union."

The Shock was made on the Universal lot for $28,000 and pulled in

$400,000 at the box office; again, Pelley's figures. Laemmle was so

pleased with the film's success, Pelley said, that he told Chaney, "You

can make for Universal anything you want."

"Mr. Laemmle," Pelley quotes Chaney, "I want to play The Hunchback of

Notre Dame."

"What?" was Laemmle's startled reaction, followed by the advice,

"There's no future in football pictures this year."

Pelley reports that Lon capably explained that Quasimodo was the

hunchback from French literature, not the quarterback for the Fightin'

Irish.

As Hunchback went into production veteran screenwriter Arthur

Statter, who had put the finishing touches on The Shock, took a

specimen of Pelley's writing to Metropolitan Pictures where it became

Her Fatal Millions (1923).

The film starred Viola Dana and was an early directing job for William

Beaudine, whose career would close more than 40 years later with Billy

the Kid vs. Dracula (1966) and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein's

Daughter.

Back in New York Pelley found his 11-year marriage falling apart.

Still suffering the heartbreak of the ensuing separation, Pelley formed

a scenario partnership with H. H. Van Loan, who shortly prepared The Fog

(1923) from Pelley's second novel. Herb Van Loan and Bill Pelley made a

financial "go" of their endeavor before Van Loan became more interested

in pursuing actress Patsy Ruth Miller.

Back in business for himself, Pelley adopted the slogan "I Write 'em,

You Wreck 'em." He started his own printing concern in New York to issue

The Plot, an illustrated digest used to pitch his scenarios.

Pelley made his break into westerns with Ladies to Board (1924) and

Sawdust Trail (1924). Tom Mix inherits an old folks home in the comical

Ladies to Board, which was the most successful of the Mix films produced

for Fox. It was also Pelley's most popular film story. Sawdust Trail

finds Hoot Gibson getting laughs as a member of a Wild West show.

Even though his productions were filled with good humor and his

pockets filled with money, Pelley was unhappy. While his cowboy heroes

always got the girl, he was broken by his own failed marriage. In

seeking to take stock of a life which had begun humbly enough in Lynn,

Massachusetts in 1890, Pelley gave in to wanderlust.

During the next two years he motored around the country, popping in

from time to time at New York or Hollywood, selling a magazine story

here, a screenplay there. Talk of communist conspirings in America were

widespread at this time. Henry Ford had not only made modern

transportation available to the average American; he had introduced

political antisemitism into the mainstream by publishing such writings

as The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. It was under such a

perceived threat of "Red" takeover that Pelley now saw his nation.

On a New York stopover in 1925 Pelley met the new lady fiction

editor at The American Magazine, to which he had been a regular

contributor. She convinced him to hang around and go over his backlog

of manuscripts with her. While in town Pelley checked in with his agent

friend Larry Giffen.

Giffen put him on to a government film project that was still in the

early planning stages. Aching for something new, Pelley went to

Washington to meet the people involved.

Initial discussion surrounded plans to overhaul the work program for

federal prison inmates. A film, it was suggested, would put the issue

before the public and help speed legislation. Pelley accompanied a

Department of Justice agent and Washington press correspondent to the

National Press Club where more informal chit-chat turned vicious.

"There's a crowd of us here who've come to accept that a crowd of Jew

financiers have put their heads together to take this country for a

ride," Pelley was bluntly told.

"In Hollywood I've heard plenty about what the Jews are going to do

to Christian American if we give them the opening," Pelley replied,

assuring his new acquaintances that such theorizing did not come as a

shock to him.

Pelley's hosts steered his search for purpose with suggestions that an

author of his voice would do well to expose the alleged Jewish plan for

world domination.

"I knew a disquiet in my spirit that was not as former moods," Pelley

said. "I wanted to believe that I had something to do in a public way

that might be worthwhile in a civic sense; but to awaken to the

actualities of a militant crusading at that time was beyond me."

He went away from Washington and the proposed film was never made.

However, in later years Pelley would write that perhaps his entire work

in motion pictures was brought about by "Kismet" so that he could make

this particular trip. Certainly many of the contacts he made on the

occasion of his visit would serve him well when the Silvershirt

sequence opened. But for the time being there were new commercial

opportunities to explore in Hollywood.

Grant Dolge had been Pelley's agent on the west coast since 1924.

Dolge also acted as manager for such celebrities as Huntley Gordon,

Blanche Sweet, Mack Swain and Kate Price. Late in 1926 Dolge mentioned

to Pelley that his actors needed someone to handle their publicity.

Taking his cue, Pelley approached his friend Eddy Eckels, who worked in

the promotional department at MGM. Soon the offices of the Pelley &

Eckels Agency opened in the Guaranty Building on Hollywood Boulevard.

(Originally written circa 1994. Article has not been corrected or reformatted since 2001. Rescued from usenet and shared here for what information may not appear elsewhere.)